The first moves of a chess game are the "opening moves", collectively referred to as "the opening" or "the book." There are a number of openings, some defensive, and some offensive; some are tactical, and some are strategic; some openings focus on the center, and others focus on the flanks; some approaches are direct, and others are indirect. Opening theory is sufficiently complex that it can take many years of study to master.

In tournament play, the moves of the opening are usually made relatively quickly. A new move in the opening, one that has not been played before, is said to be a "novelty" and "out of book."

Aims of the opening

Although a wide variety of moves are played in the opening, the aims behind them are broadly speaking the same. First and foremost, the aim is to avoid being checkmated and avoid losing material, as in other phases of the game. However, assuming neither player makes a blunder in the opening, the main aims include:

- Development: the pieces in the starting position of a game are not doing anything very useful. One of the main aims of the opening, therefore, is to put them on more useful squares where they will have more impact on the game. To this end, knights are usually developed to f3, c3, f6 and c6 (or sometimes e2, d2, e7 or d7), and both player´s e- and d-pawns are moved so the bishops can be developed (alternatively, the bishops may be fianchettoed with a manoeuvre such as g3 and Bg2). The more rapidly the pieces are developed, the better. The queen, however, is not usually played to a central position until later in the game, as it is liable to be attacked otherwise, when its value means it has to be moved, which can waste time.

- Control of the center: at the start of the game, it is not clear on which part of the board the pieces will be needed. However, control of the central squares allows pieces to be moved to any part of the board relatively easily, and can also have a cramping effect on the opponent. The classical view is that central control is best effected by placing pawns there, ideally establishing pawns on d4 and e4 (or d5 and e5 for Black). However, the hypermodern school showed that it was not always necessary or even desirable to occupy the center in this way, and that too broad a pawn front could be attacked and destroyed, leaving its architect vulnerable: an impressive looking pawn center is worth little unless it can be maintained. The hypermoderns instead advocated controlling the centre from a distance with pieces, breaking down one´s opponent center, and only taking over the center oneself later in the game. This leads to openings such as the Alekhine Defence - in a line like 1. e4 Nf6 2. e5 Nd5 3. d4 d6 4. c4 Nb6 5. f4 White has a formidable pawn center for the moment, but Black hopes to undermine it later in the game, leaving White´s position exposed.

- King safety: in the middle of the board, the king is somewhat exposed. It is therefore normal for both players to either castle in the opening (simultaneously developing one of the rooks) or to otherwise bring the king to the side of the board via artificial castling.

- Good pawn structure: this is perhaps not so important as the other aims, but it is something which should be borne in mind. A number of openings are based on the idea of giving one´s opponent an inferior pawn structure. In the Winawer Variation of the French Defence (1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. e5 c5 5. a3 Bxc3 6. bxc3), Black gives up his pair of bishops (which, other things being equal, it is usually best to hang on to) and allows White more space, but damages White´s pawn structure in compensation by giving him doubled c-pawns. Similarly, in the Nimzo-Indian Defence (1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4), the Classical Variation (4. Qc2) is specifically designed to avoid a similar fault in White´s pawn structure (he can recapture on c3 with the queen rather than the b-pawn). (It should be noted that doubled pawns are not all negative for their holder: doubled pawns on one file mean a half-open adjacent file which can be used for an attack.)

In more general terms, many writers (for example, Reuben Fine in The Ideas Behind the Chess Openings) have commented that it is White´s task in the opening to preserve and increase the advantage conferred by moving first, while Black´s task is to equalise the game. Many openings, however, give Black a chance to play aggressively for advantage from the very start.

Opening nomenclature

Early in the history of chess the lack of an adequate or widely used system of chess notation

made it very cumbersome to describe the opening moves of a game.

It was natural to assign names to sequences of opening moves to make them easier to discuss.

Opening theory began being studied more scientifically from the 1840s on, and many opening variations were discovered and named in this period and later.

Unfortunately opening nomenclature developed haphazardly, and most names are more historical accidents than based on any systematic principles.

The oldest openings tend to be named for geographic places and people. Places are frequently nationalities, for example English, French, Scotch, Russian, Italian, and Sicilian, but cities are also used such as Vienna and Wilkes-Barre.

Chess players´ names are the most common sources of opening names.

The name given to an opening is not always that of the first player to adopt it; often an opening is named for the player who was the first to popularize it or to publish analysis of it.

Eponymic openings include the Ruy Lopez, Alekhine Defense, Morphy Defense, and the Réti System.

Some opening names honor two people, such as with the Caro-Kann.

A few opening names are descriptive, such as Giuoco Piano (Italian: "quiet game").

More prosaic descriptions include Two Knights and Four Knights. Descriptive names are less common than openings named for places and people.

Some openings have been given fanciful names, often names of animals. This practice became more common in the 20th century. By then, most of the more common and traditional sequences of opening moves had already been named, so these tend to be unusual openings like the Orangutan, Hippopotamus, and Elephant.

Many terms are used for the opening as well. In addition to Opening, common terms include Game, Defense, Gambit, and Variation;

less common terms are System, Attack, Counterattack, Countergambit, Reversed, and Inverted.

To make matters more confusing, these terms are used very inconsistently.

Consider some of the openings named for nationalities: Scotch Game, English Opening, French Defense, and Russian Game — the Scotch Game and the English Opening are both White openings, the French is indeed a defense but so is the Russian Game.

Although these don´t have precise definitions, here are some general observations about how they are used.

; Game : Used only for some of the oldest openings, for example Scotch Game, Vienna Game, and Four Knights Game.

; Opening : Along with Variation, this is the most common term.

; Variation : Usually used to describe a line within a more general opening, for example the Exchange Variation of the Queen´s Gambit Declined.

; Defense : Always refers to an opening chosen by Black, such as Two Knights Defense or Kings Indian Defense.

; Gambit : An opening in which material is sacrificed. Gambits can be played by White or Black. Examples include King´s Gambit and Latvian Gambit. The full name often includes Accepted or Declined depending on whether the offered material was accepted, as in Queen´s Gambit Accepted and Queen´s Gambit Declined.

; System : A method of development that can be used against many different setups by the opponent. Examples include Réti System, Barcza System, and Hedgehog System.

; Attack : Sometimes used to describe an aggressive or provocative variation such as the Albin-Chatard Attack (or Chatard-Alekhine Attack) or the Grob Attack. In other cases it refers to a defensive system by Black when adopted by White, as in King´s Indian Attack. In still other cases the name seems to be used ironically, as with the fairly inoffensive Durkin´s Attack (also called the Durkin Opening).

; Countergambit : A gambit response that not only declines the offered sacrifice, but offers a gambit of its own. The Falkbeer Countergambit to the King´s Gambit is a well-known example.

; Reversed, Inverted : A Black opening played by White, or more rarely a White opening played by Black. Examples include Sicilian Reversed (from the English Opening), and the Inverted Hungarian.

Rarely the prefix Anti- is applied before the name, for example Anti-Marshall (against the Marshall (Counter) Attack of the Ruy Lopez) or Anti-Meran (against the Meran Variation of the Semi-Slav Defense).

Classification of chess openings

Various classification schemes for chess openings are in use. The ECO scheme is given at list of chess openings.

The beginning chess position offers White 20 possible first moves. Of these, 1.e4, 1.d4, 1.c4 and 1.Nf3 are by far the most popular as these moves do the most to promote rapid development and control of the center. A few other opening moves are also good for White but do not follow as many of the opening principles. Bird´s Opening, 1.f4, addresses center control but not development and it weakens the king position slightly. The King´s and Queen´s fianchettos 1.b3 and 1.g3 aid development a bit, but they only address center control peripherally and are slower than the more popular openings. The 13 remaining possibilities are rarely played at the top levels of chess. Of these, the best are merely slow such as 1.c3, 1.d3, and 1.e3. Worse possibilities either ignore the center and development like 1.a3 or place the knights on poor squares such as 1.Na3 and 1.Nh3.

Black has 20 possible responses to White´s opening move. In addition to the 7 best first moves for White, the moves 1...c6 and 1...e6 are also popular.

One common way to group openings is

- Double King Pawn or Open Games (1.e4 e5)

- Single King Pawn or Semi-Open Games (1.e4 other)

- Double Queen Pawn or Closed Games (1.d4 d5)

- Indian Systems (1.d4 Nf6)

- Other Black Defenses to 1.d4 (including the Dutch and the Benoni)

- Flank Openings (1.c4 or 1.Nf3 and others)

Open games (1.e4 e5)

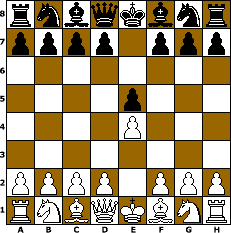

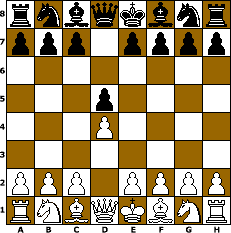

White starts by playing 1.e4 (moving his King´s pawn 2 spaces). This is the most popular opening move and it has many strengths — it immediately works on controlling the center, and it frees two pieces (the queen and a bishop). Bobby Fischer rated 1.e4 as "best by test". On the downside, 1.e4 places a pawn on an undefended square and weakens d4 and f4; the Hungarian master Gyula Breyer declared that "After 1.e4 White´s game is in its last throes". If Black mirrors White´s move and replies with 1...e5, the result is an open game.

The most popular second move for White is 2.Nf3 attacking Black´s king pawn and preparing to advance the queen pawn to d4. Black´s most common reply is 2...Nc6, which usually leads to the Ruy Lopez, Giuoco Piano or Two Knights Defense. If Black instead maintains symmetry and counterattacks White´s center with 1...Nf6 then a Petrov results.

Of the openings in this section, only the Damiano Defense is truly bad,

although the Elephant Gambit and the Latvian Gambit are very risky for Black.

The Portuguese Opening, Alapin´s Opening, Konstantinopolsky Opening, and Inverted Hungarian Opening are rare, offbeat tries for White.

Semi-open games (1.e4, Black plays something other than 1...e5)

In the semi-open games White plays 1.e4 and Black breaks symmetry immediately by replying with a move other than 1...e5. The most popular Black defense to 1.e4 is the Sicilian, but the French and the Caro-Kann are also very popular. The Pirc and the Modern are also commonly seen, and the Alekhine has made occasional appearances in World Chess Championship games. The Center Counter and Nimzowitsch are playable but rare. Owen´s Defense and St. George´s Defense are oddities, although Tony Miles once used St. George´s Defense to defeat then World Champion Anatoly Karpov.

The Sicilian and French Defenses lead to unbalanced positions that can offer exciting play with both sides having chances to win. The Caro-Kann Defense is solid as Black intends to use his c-pawn to support his center (1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5). Alekhine´s, the Pirc and the Modern are hypermodern openings in which Black tempts White to build a large center with the goal of attacking it with pieces.

The openings classified as closed games begin 1.d4 d5. The move 1.d4 offers the same benefits to development and center control as does 1.e4, but unlike with the King Pawn openings where the e4 pawn is undefended after the first move, the d4 pawn is protected by White´s queen. This slight difference has a tremendous effect on the opening. For instance, whereas the King´s Gambit is rarely played today at the highest levels of chess, the Queen´s Gambit remains a popular weapon at all levels of play. Also, compared to the King Pawn openings, transpositions between variations are more common and critical in the closed games.

The Richter-Veresov Attack, Colle System, Stonewall Attack, and Blackmar-Diemer Gambit are classified as Queen´s Pawn Games because White plays d4 but not c4.

The Richter-Veresov is played at the top levels of chess.

The Colle and the Stonewall are both Systems, rather than specific opening variations.

White develops aiming for a particular formation without great concern over how Black chooses to defend.

Both these systems are popular with club players because they are easy to learn,

but are rarely used by professionals because a well prepared opponent playing Black can equalize fairly easily.

The Blackmar-Diemer Gambit is an attempt by White to open lines and obtain attacking chances.

Most professionals consider it too risky for serious games, but it is popular with amateurs and in blitz chess.

The most important closed openings are in the Queen´s Gambit family (White plays 2.c4).

The Queen´s Gambit is somewhat misnamed, since White can always regain the offered pawn if desired.

In the Queen´s Gambit Accepted, Black plays ...dxc4, giving up the center for free development and the chance to try to give White an isolated queen pawn with a subsequent ...c5 and ...cxd5.

White will get active pieces and possibilities for the attack.

Black has two popular ways to decline the pawn, the Slav (2...c6) and the Queen´s Gambit Declined (2...e6).

Both of these moves lead to an immense forest of variations that can require a great deal of opening study to play well.

Among the many possibilites in the Queen´s Gambit Declined are the Orthodox Defense, Lasker´s Defense, the Cambridge Springs Defense, the Tartakower Variation, and the Tarrasch and Semi-Tarrasch Defenses.

Black replies to the Queen´s Gambit other than 2...dxc4, 2...c6, and 2...e6 are uncommon.

The Chigorin Defense (2...Nc6) is playable but quite rare.

The Symmetrical Defense (2...c5) is the most direct challenge to Queen´s Gambit theory —

Can Black equalize by simply copying White´s moves?

Most opening theoreticians believe the answer is no, and consequently the Symmetrical Defense is not popular.

The Baltic Defense (2...Bc5) takes the most direct solution to solving the problem of Black´s queen bishop by developing it on the second move.

Although it is not trusted by most elite players, it has not been definitely refuted and some very strong grandmasters have played it.

The Albin Countergambit (2...e5) is generally considered too risky for top-level tournament play, and the Marshall Defense (2...Nf6) is no longer played as it is thought to be definitely inferior for Black.

The Indian systems are asymmetrical responses to 1.d4 that employ hypermodern chess strategy. Fianchettos are common in many of these openings. As with the closed games, transpositions are important and many of the Indian defenses can be reached by several different move orders. Although Indian defenses were championed in the 1920s by players in the hypermodern school, they were not fully accepted until Soviet players showed in the late 1940s that these systems are sound for Black. Since then, Indian defenses have been the most popular Black replies to 1.d4 because they offer an unbalanced game with chances for both sides.

Advocated by Nimzowitsch as early as 1913, the Nimzo-Indian was the first of the Indian systems to gain full acceptance. It remains one of the most popular and well-respected defenses to 1.d4. Black attacks the center with pieces and is prepared to trade a bishop for a knight to weaken White´s queenside with doubled pawns.

The Queen´s Indian Defense is considered solid, safe, and perhaps somewhat drawish. Black often chooses the Queen´s Indian when White avoids the Nimzo-Indian by playing 3.Nf3 instead of 3.Nc3. Black constructs a sound position that makes no positional concessions, although sometimes it is difficult for Black to obtain good winning chances. Karpov is a leading expert in this opening.

The King´s Indian Defense is aggressive and somewhat risky, and generally indicates that Black will not be satisfied with a draw. Although it was played occasionally as early as the late 19th century, the King´s Indian was considered inferior until the 1940s when it was featured in the games of Bronstein, Boleslavsky, and Reshevsky. Fischer´s favored defense to 1.d4, its popularity faded in the mid-1970s. Kasparov´s successes with the defense restored the King´s Indian to prominence in the 1980s.

Ernst Grünfeld debuted the Grünfeld Defense in 1922. Distinguished by the move 3...d5, Grünfeld intended it as an improvement to the King´s Indian which was not considered entirely satisfactory at that time. The Grünfeld has been adopted by World Champions Smyslov, Fischer, and Kasparov.

The Old Indian Defense was introduced by Tarrasch in 1902, but it is more commonly associated with Chigorin who adopted it five years later. It is similar to the King´s Indian in that both feature a ...d6 and ...e5 pawn center, but in the Old Indian Black´s king bishop is developed to e7 rather than being fianchettoed on g7. The Old Indian is solid, but Black´s position is usually cramped and it lacks the dynamic possibilities found in the King´s Indian.

The Catalan Opening is characterized by White forming a pawn center at d4 and c4 and fianchettoing her king´s bishop.

It resembles a combination of the Queen´s Gambit and Réti Opening.

Since the Catalan can be reached from many different move orders, (one QGD-like move sequence is 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.g3), it is sometimes called the Catalan System.

The Torre Attack and Trompowski Attack are White anti-Indian variations.

Related to the Richter-Veresov Attack, they feature an early Bg5 by White and avoid much of the detailed theory of other queen´s pawn openings.

The Budapest Defense is not often played in grandmaster games, but it is played by amateurs. Although it is a gambit, White usually does not hold on to the extra pawn.

Other Black responses to 1.d4

There are several other defenses that can be played to 1.d4. The most common is the Dutch Defense. The Dutch is quite aggressive. Adopted for a time by World Champions Alekhine and Botvinnik, it is still played occasionally at the top level by Short and others. Another fairly common opening is the Benoni Defense, which may become very wild if it develops into the Modern Benoni, though other variations are more solid. The remaining openings in this section are uncommon. The Englund Gambit is a rare and dubious sacrifice. The Polish Defense has never been very popular but has been tried by Spassky, Ljubojevic, and Csom, among others. The Kangaroo Defense, also known as the Keres Defense, often transposes into the Dutch, Nimzo-Indian, or Bogo-Indian.

Flank openings (White plays something other than 1.e4 or 1.d4)

The English is the most popular opening in this group, but the Réti and King´s Indian Attack are also well respected.

Most of the others are considered distinctly offbeat and are rarely used by strong players, although Larsen´s Opening and the Sokolsky Opening are occasionally seen in grandmaster play.

Benko used 1.g3 to defeat both Fischer and Tal in the 1962 Candidates Tournament in Curaçao.

If White opens with 1.Nf3, the game often turns into one of the d4 openings by a different move order (this is known as transposition), but unique openings such as the Réti (1.Nf3 d5 2.c4) and the King´s Indian Attack are also common.

Barnes Opening (1.f3) is probably the worst opening move for White. It takes away the most natural development square for White´s knight on g1, weakens the vulnerable f2 square near the king and neglects development.

See also Fool´s mate.

See also

References

- De Firmian, Nick (1999). Modern Chess Openings: MCO-14. Random House Puzzles & Games. ISBN 0-8129-3084-3.

- Nick de Firmian is a 3-time U.S. Chess Champion. Often called MCO-14 or simply MCO, this is the 14th edition of the work that has been the standard English language reference on chess openings for a century. This book is not suitable for beginners, but it is a valuable reference for club and tournament players.

- Kasparov, Garry, and Raymond Keene (1989, 1994). Batsford Chess Openings 2. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-3409-9.

- Garry Kasparov was the World Chess Champion from 1985–2000. This book is often called BCO 2 and is intended as a reference for club and tournament players.

- Keene, Raymond, and David Levy (1993). How to Play the Opening in Chess. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-2937-0.

- Raymond Keene is a former British Chess Champion and a noted chess author. This is an introductory book suitable for beginning to intermediate level chess players. It is not a reference covering all opening theory, but instead explains the ideas behind several popular opening variations.

- Nunn, John (ed.), et al. (1999). Nunn´s Chess Openings. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-8574-4221-0.

- John Nunn is a former British Chess Champion and a noted chess author. This book is often called NCO and is a reference for club and tournament players.

- Sahovski Informator. The Encyclopedia of Chess Openings

- This is an advanced, technical work in 5 volumes published by Chess Informant of Belgrade. It analyzes openings used in tournament play and archived in Chess Informant since 1966. Instead of using the traditional names for the openings and descriptive text to evaluate positions, Informator has developed a unique coding system that is language independent so that it can be read by chess players around the world without requiring translation. Called the ECO, these volumes are the most comprehensive reference for professional and serious tournament players.

- Znosko-Borovsky, Eugene A. (1971). How to Play the Chess Openings. Dover. ISBN 0-8129-3084-3.

- Eugene Znosko-Borovsky was a noted Russian chess teacher. This inexpensive reprint is a translation of a Russian book originally published in 1935. Although most of the specific variations given in the book have been obsolete for many years, the book´s discussion of general opening principles and survey of the major opening systems can still be useful for beginning players. Club and tournament players will need a more up to date reference.

For a list of openings as classified by the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings, see List of chess openings.

|